The Charlotte Observer, April 23, 1996

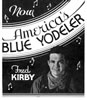

Kids' hero, TV cowboy Fred Kirby dies at 85

By PAT BORDEN GUBBINS, Staff Writer

Charlotte's singing cowboy has hung up his six-shooters for good.

Fred Kirby, loved by fans in the Piedmont for his yodel, his horse Calico and his kindness to children, died Monday, April 22, 1996.

He was 85 and died in his sleep at his home in Indian Trail.

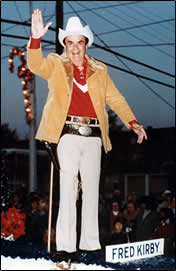

Kirby, with his cowboy hat shading a set of dark eyes and a gap-toothed grin, was a local hero for children and adults alike.

He began his broadcasting career on radio in the 1920s and appeared on television before most Americans had ever even heard of it. By the time he had retired from Charlotte's WBTV in 1976, he had earned the title of the longest-running children's show host in America.

"When Fred Kirby spoke to you, it was like you were the only kid in the world," said Phyllis Keels, a 37-year-old data processor from Salisbury. She appeared on Kirby's "The Little Rascals" television show in the '60s when she lived in Shelby. She had won a bicycle. "With a banana seat and butterfly handlebars. There was just something really wholesome about Fred Kirby."

After a radio career that included a coast-to-coast CBS show titled "Carolina Calling," Kirby started his television career in 1951 on WBTV with "Junior Rancho." It was followed by "The Little Rascals," "Looneytune Jamboree," "Ricochet Round-Up" and "Whistlestop," all on WBTV.

If you missed him on the airwaves, you might have seen him riding Calico in the Carrousel Parade on Thanksgiving Day, upholding the law as make-believe marshal at the Tweetsie Railroad theme park near Boone, or visiting children in hospitals across the country.

His audience kept on loving him, well into adulthood. There are plenty of Carolinians older than 30 who can still sing: "How . . . we . . . love the Little Rascals, Little Rascals, Little Rascals . . . " and who recall Kirby's pardner Uncle Jim, Jim Patterson, who died in 1986.

Shannon Reichley, WBTV news director, remembers the stir Kirby created last year when he stopped by the station and was spied by a church group from Salisbury.

"He had his cowboy hat on," Reichley said. "Those forty-something folks saw him, and they went nuts. It was a very touching thing."

For any child who loved to play cowboy, Kirby was the real thing.

Union County Sheriff Frank McGuirt remembers the first parade he attended in uptown Charlotte when he was an elementary school student in the early 1950s.

Parade grand marshal William Boyd, who starred in the "Hopalong Cassidy" TV series, got polite applause, said McGuirt. "And then Fred came along, and the crowd went wild."

Ratings in February and March 1972 showed more than 200,000 folks tuned in to see Fred Kirby and "The Little Rascals," which came on Sundays at noon. At least one minister was known to let his congregation leave early so they could catch the show.

Kirby took his responsibility to children seriously. "I try to be a good example," he once told a reporter. "I don't drink or smoke, and I don't go places I wouldn't take my 12-year-old daughter, Nanette."

He made himself accessible. He visited hospitals, made endless personal appearances and invited kids to join him on the air.

For many, one of the great joys of childhood was to appear on "Junior Rancho."

Parents watched a monitor in another room, while Kirby had his small guests perch on the split-rail fence that made up his set.

He typically pulled out his guitar, did his trademark yodel and sang a couple of songs. He walked along the fence and talked with some of the kids, who were electrified to be in his presence. Kirby favored colorful cowboy shirts, loaded with fringe and fancy embroidery.

McGuirt never got to be on the show, but he was a proud member of the Junior Rancho Club. He had a special decoder that went with the membership.

"He aired a secret message, and you had to have the decoder to get the message," McGuirt said. "It was usually something about child safety or 'Do your homework.'"

When he grew up to become sheriff, McGuirt was surprised when Kirby sent him contributions for each of his four campaigns. "He lived in Indian Trail," just inside Union County, McGuirt said. "He seemed to become a fan of mine, after I was a fan of his. I hope so, anyway."

Kirby was born in Charlotte on July 19, 1910, one of 10 children of a Methodist minister.

His mother taught him to play on a $7.50 guitar. When he was 17, Kirby's family lived in Florence, S.C. On a trip to Columbia, the young Kirby visited radio station WIS, where he was invited to play and sing. That earned him his first radio job.

After eight months, he moved to WBT, where he starred for the next 10 years.

One of his earliest idols was the Father of Country Music — Jimmie Rodgers, known for his yodeling.

"I tried to emulated his 'Blue Yodel,'" Kirby said in an interview in January, one of his last. "Somebody told me, 'Fred, why don't you stop emulating Jimmie Rodgers and start emulating yourself?' So I changed. And I started writing my own songs."

He would go on to write more than 500 of them, including his 1946 million-selling "Atomic Power," about the awesome power of nuclear energy. But his favorite was "The Old Country Preacher," which he wrote it memory of his father.

Kirby often performed on WBT radio with a country band called the Briarhoppers. One band member, 86-year-old Don White (of Indian Trail), met Kirby on WBT radio in 1935. Four years later they got together as "The Smiling Cowboys" on radio station WLW in Cincinnati. Their material in cluded Kirby compositions like "My Old Saddle Horn Is Missing."

Later, they changed their name to the Carolina Boys.

"We did sing-through-your nose country," White said. "Fred was a nice guy to work with. He had a good sense of humor."

Kirby left Charlotte for several years and traveled to stations as far away as Chicago and St Louis.

During World War II, Kirby met some of the most famous names in American show business, including Doris Day. U.S. Treasury Secretary Henry Morganthau Jr. proclaimed Kirby "The Victory Cowboy" for helping to sell millions of dollars in war bonds and raising money for charities.

Over the years, Kirby had eight horses named Calico. Horse and rider were well-known to visitors at Tweetsie Railroad, where for 30 years, Kirby was a part-owner and marshal. Later, he was a spokesman for the wild-West attraction.

Kirby often performed at nursing homes, Special Olympics events and children's hospitals.

A girl he had never met underwent spinal surgery in May 1972 at the orthopedic hospital in Gastonia. Before she went under anesthesia, the girl was asked if there was anything she wanted when she awoke.

"To see Fred Kirby," she said. He was there when she opened her eyes.

Kirby spent most of his time in his later years watching TV and reading the Bible.

Survivors include his wife, Mary Burke Kirby, four daughters, eight grandchildren and several great-grandchildren.

Memorial services will be at 11 a.m. Wednesday at Park Road Baptist Church. Visitation is 7 to 9 p.m. today at McEwen Charlotte Chapel and at the church. Memorials may be made to Holy Angels, 6600 Wilkinson Blvd., Belmont, NC 28212, or to the charity of the donor's choice.

"Happiness has been my trademark," Kirby said in January, looking back over his career. "A smile to everybody."

Staff writers Joe DePriest, Kay McFadden and Tony Brown contributed to this article.

Not into our ears, exactly. If the subject is too painful or tender, they'll leave a message on a newsroom phone at a time they suspect no one will be around to answer in person.

Not into our ears, exactly. If the subject is too painful or tender, they'll leave a message on a newsroom phone at a time they suspect no one will be around to answer in person. Fred used to ride his horse calico in the parade...Right in front of our float with all the channel 3 personalities on it. Folks would go nuts over Fred...And then they'd get a slow look at the rest of us.

Fred used to ride his horse calico in the parade...Right in front of our float with all the channel 3 personalities on it. Folks would go nuts over Fred...And then they'd get a slow look at the rest of us.