Sometimes the "floor" became the "ground," when they moved away from the studio. These events were called "remotes."

Sometimes the "floor" became the "ground," when they moved away from the studio. These events were called "remotes."

Among the unsung heroes at WBTV were the men and women of the Floor Crew.

In the studio they erected, dressed and lit the sets, arranged the props, operated the cameras and TelePrompTers, and—with their initiative, expertise and good taste, not to mention hustle—made the talent and the show look good. Then, while the director, the talent and the sales staff were getting most of the credit for a job well done, and sipping cocktails with the sponsors in the Jefferson Suite, the crew members were breaking their butts striking and storing the set, cleaning up the studio, and setting up for the next session.

In the studio they erected, dressed and lit the sets, arranged the props, operated the cameras and TelePrompTers, and—with their initiative, expertise and good taste, not to mention hustle—made the talent and the show look good. Then, while the director, the talent and the sales staff were getting most of the credit for a job well done, and sipping cocktails with the sponsors in the Jefferson Suite, the crew members were breaking their butts striking and storing the set, cleaning up the studio, and setting up for the next session.

For location shoots, they loaded and drove the grip trucks, strung hundreds of yards of electric and camera cable, erected scaffolds, hoisted the cameras, lights, reflectors and much other grip and gaffer gear, kept the generator gassed up and working, laid and leveled the dolly track, ate bad food, doubled up in cheesy motel rooms, and the million other things that had to be done to pull off a successful "remote." It was grueling work.

But that was their job. They accepted it, and did it with enthusiasm and good grace. So, as you view these old photos and read about them, give a salute to those dedicated people who played a tremendous role in the success of WBTV.

(Disclaimer: There were other groups that played as great a role, and as we gather their photos we'll celebrate them too. The engineers, for example, worked right alongside the aforementioned crew, configuring, maintaining, calibrating and operating the complex equipment, and getting the signal out to the waiting world.)

It was 1952, on the Susie McIntyre kitchen set. Susie was Betty Feezor's predecessor as Channel 3's maven of cooking and stuff. Here, young Doug McDaniel, displaying that lean and hungry look, is on the left. In the white shirt is Julian Massi (obviously defying child labor laws). That's handsome Max Davis in the sweater, and floor supervisor Charlie Lineberger on the end.

This was called a "standing" set, for it was always left standing, and never "struck," because—in this case, being a kitchen set—it was hooked up to the city water and sewer systems, and the refrigerator contained real food. It would have been too much trouble to move it, so it was built snuggly against a studio wall, to allow most of the room always to be available for other productions. Most sets, though, were disassembled immediately after use and removed for storage in the "prop room."

Secrets revealed: Our kitchen sets always had a window over the sink to give them a touch of realism, and placed outside the window was fake foliage, or a photo mural of some landscape, or both. Some TV stations (and you know who you are) were too chintzy to go to that trouble. They'd just keep the blinds closed.

Photo courtesy Doug McDaniel

For many years Betty Feezor was the queen of the midday airwaves. It seemed the entire domestic world (within WBTV's range) stopped and tuned in for her recipes, interviews, helpful hints, and her show-and-tell sessions like the one in the picture.

Her kitchen set was over to her right, and this small area of Studio 1 was used for her non-cooking segments. Betty would arrive around 10:00am and meet with the director and crew, disclosing what she had planned for the day. Whatever was needed for the show was then gathered, positioned and lit—her sewing machine; a sit-down area for an interview, with comfortable chairs, a lamp and perhaps a potted palm; a piano for former President Nixon to play. Meanwhile, in WBTV's larger Studio 2, another contingent of the crew was getting ready for the noon news or some other live production later that afternoon. Doug McDaniel is manning that sleek RCA tri-lens monochrome camera on its patented pedestal. No color yet.

Secrets revealed: If you ever watched the show, did you ever wonder how they got those overhead close ups—looking straight down—of Betty mixing cake batter, or preparing a turkey for roasting? There was no camera attached to the ceiling; cameras in those days were much too large and heavy. Suspended over her work area was a big rectangular mirror reflecting every move she made. One of the floor cameras would be pointed upward into the mirror, capturing close ups of her hands and utensils. Now you know.

Photo courtesy Doug McDaniel

Once it was thought that having the crew dress like service station attendants would add a touch of professionalism to the operation, and promote an esprit de corps within the group. After all, didn't Alan Newcomb wear such an outfit on Atlantic Weather, with a uniform cap and leather bow tie?

Actually the crew was a very professional, tight-knit, cohesive group, with all the attributes required to make WBTV the premier station in the area. Later, our crew people graduated to khaki pants and matching knit shirts with the station's logo above the pocket.

This group is on the "Junior Rancho" set, either prior to Fred Kirby's arrival at the studio or just after his departure. Hank Warren was always lurking about with his camera to capture the moment, and the crew was always eager to pose. Gene Birke is on the left, and, sitting in what is someone's idea of a chuck wagon, are Doug McDaniel, Julian Massi (somewhat older and wiser now) and Bob Suttle. Gene went on to become a director (of programs, not the company), Doug became a lighting expert and Julian went into sales (where the money is).

It all looks so primitive. How did we ever fool the little kiddies? Or did we?

Photo courtesy Doug McDaniel

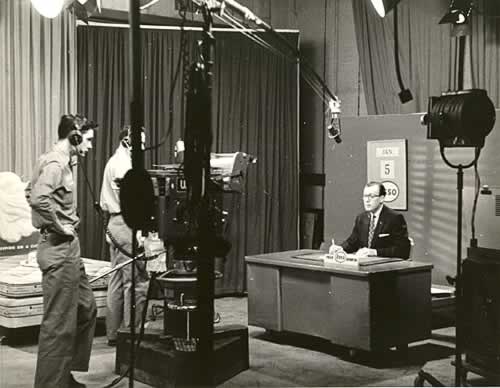

Close quarters. Doug Mayes was for many years your Esso Reporter. Here his news "set" is jammed in among other studio activities, in this case a mattress commercial that had aired live just before the newscast, or was scheduled afterwards. The crew had to be adept at adjusting quickly from one setup to another. (There is reason to believe this photo was taken on January 5th.)

In those days the local early eveing newscast was only 15 minutes long. It was followed by another 15 minutes of the CBS News with Douglas Edwards. CBS's widely acclaimed news department was still focused mainly on radio news. They hadn't yet determined that TV was going to catch on, so CBS's heavy hitters ignored that tacky upstart medium called television. Most of CBS's news footage was provided by an outside outfit called Telenews Productions. It was awful—usually a day or more old, and resembled the news reels we saw at the picture show.

For the totally uninitiated, each crewman wore a headset to communicate with the director in a booth somewhere away from the studio, usually on another floor of the building. The cameramen (here it's Don McDaniel) would hear instructions such as "Camera One, tilt up just a hair...that's good" or "Camera Two, you're clear—go to a head-and-shoulders of Doug." The director would also be talking to others involved in the broadcast: "Projection, standby to roll film on Chain One" or "Video, can you bring up the level on the super card on Camera Three."

The other crewman in the picture, partially hidden by the balance weight of the sound boom, is controlling the speed of the script running through the 'prompter, keeping pace with Doug's delivery. In later years, overhead mikes became old fashioned, when tiny, easy-to-conceal mikes were developed, which could be pinned to the announcer's lapel.

Secrets revealed: Notice the "venetian blind" light pattern on the flat behind Doug. Great care was taken to give the scenes more depth and contrast, and to make the shot more interesting. A splash of light—and in later years a splash of color—could make all the difference between a visually appealing shot and a bland one.

Photo courtesy Don McDaniel

If only these walls could talk. In TV production, walls are called "flats," heavy canvas stretched over lightweight 2" x 2" wooden frames that are eight or 10 or 12 feet wide. They are painted—and repainted—to the desired color of their next incarnation. In the old Wilder Building studio in the first years of WBTV, the prop room was down two flights of stairs that had a 180° turn. Luckily, those early flats were made of muslin and were only about four feet wide. Flats are braced in an upright position and clamped together to create corners and ells.

In the "new" building on Julian Price Place the prop room was conveniently located just outside the studio doors. Sometimes a set would require a different look than could be effected by painted canvas, so Floyd Grass, our woodworking wizard would build a new flat using some other material, such as wood paneling or simulated brick or stucco. Hopefully, any new set piece would be so generic that it could be used over and over.

In the photo, Joe Young is on the left, Bob Crocker is in the center, and Doug McDaniel is clutching a fake parrot, perhaps a prop for some kids' show. Joe Young went on to head the company's research department, where, among other things, they analyzed ratings data and audience trends.

Photo courtesy Don McDaniel

Kids' shows were big in early television, and WBTV always had one or more on the air or in the works. Judging by the familiar cactus in the background, this is likely Fred Kirby's "Junior Rancho," maybe the earliest of his many series. This and other WBTV shows, like "Three Ring Circus," had studio audiences of from 20 to 50 wide-eyed children, like the one sitting on the right. It would be the duty of someone on the crew to shepherd the little ones to their seats, distribute trinkets, candy and other favors, and cue them to applaud and scream wildly at the least little thing. (The sugar in the candy helped keep them in a frenzy.)

Once the show was over, and their services no longer needed, the kids were herded out of the studio into the arms of their waiting mothers, and their mess (paper cups, candy wrappers, used gum) would be cleaned up by—you guessed it—the crew.

The station kept a big helium tank in the prop room exclusively to fill balloons for the little ones. It was inevitable that every new station employee, at least once, when passing by the helium tank, would fill their lungs with the gas and go around talking funny. Then, when they noticed that nobody else was laughing, that would be the end of that, until the next new employee came along.

In the photo, standing, from left, are Joe Boston, Don McDaniel, Virgil Torrence, Julian Massi, and Fred Kirby.

Secrets revealed: the guy in the Indian garb is probably not a real Native American.

Photo courtesy Don McDaniel

If it was springtime it must be time for a visit to Tweetsie Railroad, the theme park in the North Carolina mountains, to produce a special Arthur Smith Show, a commercial, or a Fred Kirby segment. And, while they were at it, the production team might then move all the equipment over to Hugh Morton's nearby Grandfather Mountain and capture the stunning scenery.

The man at the extreme left of the photo is likely Clyde McLean, who was the announcer and spokesman on most of Arthur's shows. On the camera nearest the engine, the operator looks to be Ken Furr, with Virgil Torrence as stage manager standing beside him. The middle camera is "locked off" on a shot, and it's operator, Doug McDaniel, is standing by for further instructions. That appears to be Reggie Dunlap running the nearest camera. The man on the right is unidentified, perhaps he's an employee of the park. As the train's last car passes, Tommy Faile or Wayne Haas might be revealed standing on the other side of the track, guitar in hand, ready to perform. Virgil would cue him and he'd break into song.

Fred was a regular performer at Tweetsie on weekends. He would ride around on the docile Calico, have his picture taken by hundreds of his little fans, and "shoot" a few redskins and train robbers. On his TV shows he would always tout his upcoming appearances at the park. Tweetsie's management was always extremely cooperative, the TV exposure was good for business.

When all the fun was over, the equipment would be carefully packed up for the 90-mile trip back to Charlotte. And just before the next Spring rolled around, excuses would be made for another excursion to Tweetsie Railroad. Nice work if you can get it.

Photo courtesy Jim Scancarelli