Headphones similiar to those worn by WBT's Don Russell.

Headphones similiar to those worn by WBT's Don Russell.

|

By James K. Flynn |

Anyone who has ever worked in radio and television can speak of defining moments in their careers, whether they were on the air or behind the scenes in engineering, traffic or sales. Get-togethers are always rife with tales of daring-do. For us on-air types, these typically consist of run-ins with management, great interviews, who did what shift when, and that all time favorite, words that should not be said... that were.

We also gauge our life at the microphone from a historical sense. Over the course of 15 or 20 years, news of the turmoil of this country and the world are filtered through us to our listeners and viewers. These events cannot help but leave imprints on announcers, both good and bad. Herb Morrison isn’t a name that most people recognize until you tell them he was the guy on the air in 1937 when the Hindenberg went up in flames in Lakehurst, NJ. His engineer that day, Charles Nehlsen, is another name mostly lost to history. But, as it should be, the event has overshadowed the reporters.

I’m sure there are broadcasters who can point to the Kennedy assassinations, and King’s, as the focus of their days on air. The dismantling of the Berlin Wall, 9-11 and the World Trade Center and, for me, the Challenger disaster are all moments that can help define a career.

While all these events affect announcers, unless you were directly involved at the location— like Mr. Morrison—there is still an almost necessary detachment that allows us to perform our jobs in a professional manner. It’s when the disaster hits home—and we can still deliver the news, service and, yes, entertainment—that we can point with pride at a job well done.

|

Hugo hits Charleston |

Such was the case with Hurricane Hugo. Who knew a hurricane could reach Charlotte? Lots of rain, yes. Probably some wind. But Hugo was still a hurricane when it reached Mecklenburg County in September of 1989.

The power was already out when I got up at 4:00 AM that Friday morning. Usually, I spent a half hour on the computer, writing and checking the news before heading for the station for a 5:30 air time. Since there was no juice to feed my electronic habit, I left early. The rain and the wind were strong, but I had no idea I was driving into work through a hurricane.

By the time I arrived at 1 Julian Price Place, the engineering staff, along with Tom Desio who was on overnights, were trying to get power to the board. The transmitter had it’s own power source, but powering the board required ingenuity. Orange drop cords snaked down the hall, out to generators in the loading dock.

|

| It came tearing across the low country, roared into the Piedmont, and showed its "dirty side" to Charlotte. |

My partner, Don Russell, was already on task as well. Don liked to get to the station early, read the papers and check the wires. With no power, the lights on the phone that told us of incoming calls were dark, so Don, along with everything else, was randomly pushing lines to see who was calling in.

An extremely important part of the morning show, even in good weather, was our Accu-weather guru, Dr. Joe Sobel. We had a limited number of sockets to plug things into, so the piece of equipment that allowed phone calls on the air wasn’t a priority. (This was just a few years before the advent of cell phones.) We got Joe on the air by my holding the earpiece of the nighttime producer’s phone headset inches away from my microphone. Through occasional bursts of feedback, Joe was on the air.

My most vivid memory of that morning came just after 6:00 AM. One of the landmarks of the building was a large, beautiful old dogwood that grace the patio just outside the Pine Terrace dining room. The strongest winds and rain of the morning were pounding the huge picture windows of the studio. Suddenly, the tree slammed against the window—two stories up—and disappeared into the darkness.

The rest of the day is a blur. Delineation of air shifts disappeared. We stayed on until H. A. Thompson could make it in, and all the announcers came in as needed. Of course, as an air staff, we were used to handling weather emergencies, but mainly on the level of school and business closings for snow. Experience and professionalism paid off. Examples of what could only be classified as heroic measures came to light, the most memorable one being Engineer Bob White’s trip to the transmitter site on Nations Ford Road during the height of the storm. Pulling into the parking lot, Hugo’s winds toppled the massive Tower A, just missing Bob’s car.

Over the next days and weeks, WBT—and all the radio facilities in the region—stepped up with what the FCC originally sited as a basis for granting licenses: serving in the public interest. Information on everything from directing power crews to where they were needed, to where listeners could find ice made it on air. Everyone at the station—air staff, engineering, sales, promotion, traffic and management—rolled up their sleeves and ignored the clock to keep the station working and serving the public.

Only one of WBT’s three towers remained standing. With special dispensation from the FCC, we were allowed to remain on a daytime pattern, so B Tower sent our signal over a wider, localized area.

Television covered the scope of the damage magnificently. But Radio became the cathartic release Charlotte desperately needed. The phone lines were up and open. What had been a lifeline for many during and immediately after Hugo, blossomed into forum of hope and reconstruction. A week after the storm, with power returned to the building, my own healing moment occurred in the production room after our Saturday shift. I wrote, composed and recorded "Chainsaw" in two hours that morning. Before Christmas, we had sold 2,000 cassettes of the song, the proceeds split between the Red Cross and our Penny Pitch Children’s Charities.

But the one thing that crystallizes that time for me came two weeks after the storm. My wife was speaking to a friend of hers at school one day. The woman spoke of spending that morning, huddled with her two children in a downstairs bathroom—a flashlight and a transistor radio the only comfort in the darkness. Her husband was out of town. She listened as trees crashed around and into her house. The storm passed. "But," she said, "it was when I heard your husband’s voice...that’s when I knew it would be alright."

To serve in the public interest.

Thanks to Don Russell, Mary June Rose and Bob White for their help in remembering salient details.

|

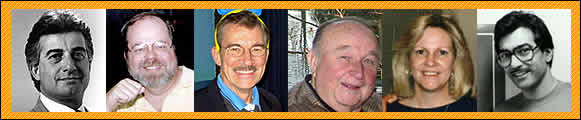

| Only a few of WBT's Hugo All-Stars From Left, Tom Desio, James K. Flynn, H. A. Thompson, Henry Boggan, Mary June Rose, Don Russell WBT staff photos courtesy Mary June Rose |

|

For several weeks after Hugo hit everyone was in a frenzy to find a chainsaw to clear his yard. Rumors flew: "Home Depot is getting a truckload of saws tomorrow!" "Lowe's has two left!" Their prices escalated wildly. Fistfights occurred over the last available one. A man's first obligation was to feed his family. His second was to GET A CHAINSAW! Of course, few of the hundreds who bought one had ever touched a chainsaw in their lives, consequently emergency rooms enjoyed a landslide business.

All this was the basis for James K.'s unforgettable "Chainsaw," a welcome touch of humor for WBT's exhausted listeners who for weeks requested that it be played over and over.

Today, in barns and sheds all over the Carolinas, way in the back under layers of broken rakes, nearly-empty paint cans and other hard-to-part-with junk, there sits a still-shiny, slightly-used, low-milage and very expensive chainsaw—untouched since October 1989.