Coleen "Fuzzy" Helvesten was a script and promotion writer for both radio and television for her entire career. (She and Norman Prevatte were married for a few years in the '50s.)

Coleen "Fuzzy" Helvesten was a script and promotion writer for both radio and television for her entire career. (She and Norman Prevatte were married for a few years in the '50s.)

|

|||||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

||

By LEW POWELL

Staff Writer

Thirty-five years ago today at noon, WBTV signed on the air as the first television station in the Carolinas. Announcer Jim Patterson read a brief statement that concluded, "Now we present test pattern and tone for set adjustment."

Norman Prevatte, a young announcer at WIST radio, was leaving the Liberty Life Building (now One Tryon Center) on his way to lunch. "There was a furniture store where the Marriott is now," Prevatte recalls. "A crowd of people was standing there, watching the test pattern on a television set in the window."

Prevatte had seen the future, and it was not radio. Within a few months he had taken a cut in salary to work at Greensboro's new WFMY-TV. There he became interested in production, and in March 1951 he returned to Charlotte as WBTV's first producer and director.

For the first few months here Prevatte's main responsibility was to drive a van with canvas bags of film back and forth between Charlotte and the WBTV transmitter at Spencer Mountain in Gaston County. The coaxial cable to New York had been completed in 1950, bringing WBTV live network programming for the first time — the North Carolina-Notre Dame football game was the debut attraction — but live local programming wouldn't begin until Sept. 30, 1951.

That first show, staged by Prevatte in a studio in the old Wilder Building on South Tryon Street, introduced the station's talent staff.

That first show, staged by Prevatte in a studio in the old Wilder Building on South Tryon Street, introduced the station's talent staff.

He still has the original script — half a dozen handwritten legal pages. It began, "This is a television studio ...." The next words the audience heard resulted from a camera mishap — a panicky "Come on back! Come on back!" followed by "I can't, dammit, I'm stuck!"

WFMY had owned one camera — one more than WBTV — so Prevatte, only 24, ranked as the undisputed TV authority on a staff of old hands from WBT radio. "I really had no background," he says, "but I was the only one who knew how to switch the pictures."

(Now 57, Prevatte returned to the station last year as a producer-director in creative services.)

There were perhaps 1,000 TV sets in WBTV's viewing area when it signed on. By 1952 that number had shot past 100,000. "TV was a status thing," Prevatte says. "It was a luxury a people had to have — it wasn't like, say, the home computer today. There was tremendous saturation, very quickly. We'd go into the mountains, and there would be a shack with a rickety antenna.

"You'd see people watching unbelievably bad pictures — snow, with just a faint image every now and then. It was the kind of attraction every day that the moon walk or the Ruby-Oswald killing had in later years. It was almost hypnotic. TV trays became big things — people just wanted to come home and watch television."

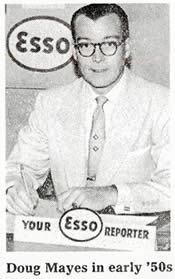

WBTV's talent in the early years, mostly drawn from WBT radio, included many names still familiar today — Jim Patterson, Clyde McLean, Doug Mayes, Fred Kirby, Bob Raiford, Arthur Smith.

"We were all looking forward to television," says Prevatte. "Everything was roses. We'd all be rich and famous .... There was even a $2.50 clothing allowance every time you were on the air. You could get your suit pressed, a shave, a haircut."

The transition was not always smooth. "These guys, as announcers, were the best in their field," says Prevatte. "Their aim had been to work at WBT, and they had reached this pinnacle on their own. Now here I was, a wet-behind-the-ears kid, telling them when to start, stop, slow down, speed up, move. And they had to learn to memorize." (WBTV didn't install TelePrompTers until the mid-'50s.)

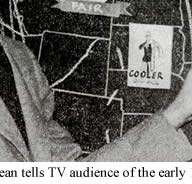

"Television made Clyde McLean, one of the lesser lights on WBT, a star, he was our best talent on television from the first day," says Prevatte. "He had a very good mind, and he could digest a piece of copy. McLean was special.

"Before television, the weather was a total throwaway — 'Looks like it'll be fair and warmer tomorrow.' The weather became a commodity when television realized it could be sold to a sponsor. We had to make more of it. As Clyde was learning, the audience was also learning about things like cold fronts. He built an enormousfollowing."

Conversely, some big names couldn't make the change to the more complex demands of television.—Kurt Webster had a terrible time," he says. "He was the hottest property on BT, but he never could adapt." (Webster, who continued his career in radio, television and advertising in Virginia, died two years ago.)

Ratings didn't become a major factor until years later when WSOC-TV and other competitors sprang up. But we still knew when there was an audience there," he says. "You had to judge by whether your friends and neighbors saw it.

"The most popular show was Fred Kirby's 'Junior Rancho.' You could watch your children or your neighbors' children on television. It's hard for people today to understand what a miracle that seemed."

Prevatte's friends in the Little Theater would kid him about un-polished shows like "WEE-TV," a predecessor of the nationally syndicated "Arthur Smith Show." "They'd say they couldn't believe what they had seen," he says, "but they had seen it. They remembered every song sung, every word spoken."

A particular favorite of Prevatte was "Nocturne," a live jazz show hosted by Bob Raiford and featuring Loonis McGlohon on piano. "To this day," he says, "that is the best ongoing show I was ever a part of."

The news was only 10 minutes long and relied mostly on wire-service copy and Fox-Movietone newsreels. Film of Saturday sports usually didn't reach the air until Tuesday.

Doug Mayes became famous as the Esso Reporter, the Piedmont's first anchorman. "Kids today laugh at it," Prevatte says, looking at an old publicity still of Mayes on the simple set. "There was a desk with a plaque on it and a calendar behind. A shadow pattern, like venetian blinds, in the background. That's all. No tricks.

"We were the only game in town for a long time. By the time Channel 9 came on the air (in 1957), we had a big head start. Doug and Clyde were entrenched, especially in the communities around us, where people don't change as much."

Prevatte, who now works with an array of sophisticated electronic tools, looks back with a mixture of warmth and amazement. "We all worked 80 hours a week," he says. "Everything was a major undertaking. We didn't have the good sense to know what we couldn't do."

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

||

Reprinted with permission by The Charlotte Observer. Copyright owned by The Charlotte Observer.