Floyd Grass was the company's cabinet maker, carpenter, set builder and prop creator. In his JP work shop, in the "Metron" building behind the studios, he regularly performed minor miracles.

Floyd Grass was the company's cabinet maker, carpenter, set builder and prop creator. In his JP work shop, in the "Metron" building behind the studios, he regularly performed minor miracles.

Which came first, videotape or film?

Ask that question of the folks at Jefferson Productions, a Charlotte, N.C., producer of TV commercials, and the answer might surprise you.

Ask that question of the folks at Jefferson Productions, a Charlotte, N.C., producer of TV commercials, and the answer might surprise you.

The division of Jefferson Pilot Broadcasting Company was organized in 1962 for the sole purpose of producing videotaped commercials. A film unit wasn't added until eight years later at the behest of sponsors. Film production now accounts for some 35 percent of the work done by Jefferson Productions.

Though film and tape units are housed and operated independently, the company's four salespeople sell film and tape capabilities jointly to clients, primarily advertising agencies. Since clients usually have decided on the medium already, the shared sales effort simply boosts sales for both film and tape, says Film Production Manager Reno Bailey.

|

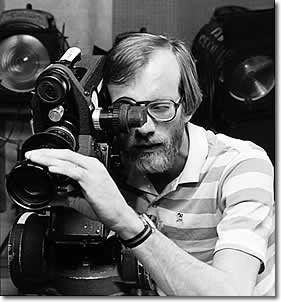

| Bob Newcomb, Director/Photographer, wraps up an in-studio commercial. The Charlotte, N.C., film production unit enjoys handling a wide range of assignments from dramatically lit, intricate tabletop action to on-location wilderness shoots. |

"If an agency or sponsor needs something very quickly, or if they are planning to shoot a large number of stand-up commercials—say a talking head promoting aspirin—they will generally choose videotape," says Bailey. "But, if they really want to glamorize their products, they usually will choose film."

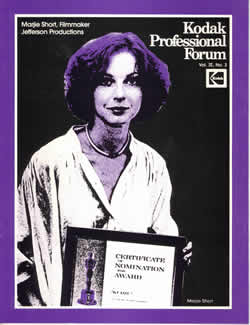

Glamour is very important to many of the company's customers, which includes Jaguar, Lincoln-Mercury Capri, Singer and Germaine Monteil Cosmetics, to name a few. A Jefferson film commercial for Capri and New York advertising agency Kenyon-Eckhart were among the finalists in the 1977 competition for the CLIO Award for Cinematography [Editor's Note: Incidentally, all 59 U.S. Clio Award-winning television commercials for 1978 originated on film.] Another Jefferson film for the National Auto Parts Association (NAPA) ranks among the top eight percent of all commercials ever tested by Burke Marketing Research for day-after recall. The Jefferson medium-budget commercial rated 44. The highest rating ever achieved—a 56—went to a one-quarter-million-dollar extravaganza.

Jefferson's ability to produce memorable film commercials at a lower-than-average cost is one reason the company's business with prestigious New York, Los Angeles, and Chicago advertising agencies is steadily climbing, Bailey says.

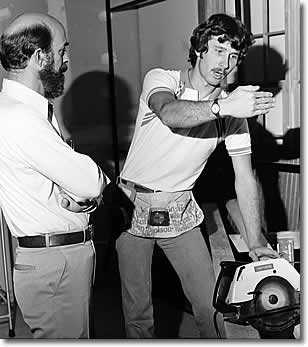

"Our Charlotte location gives us a competitive advantage because everything costs less—sets, props, crews, etc," he points out.

But quality isn't sacrificed, he adds. The film unit has seven full-time staffers. Most assignments are handled with a six- or seven-person crew with free-lance talent used for sound recording, location-scouting, make-up, etc. About 75 percent of its filming is done on location. For example, the Lincoln-Mercury Capri commercial, a CLIO nominee, was filmed at Lion Country Safari in Florida.

|

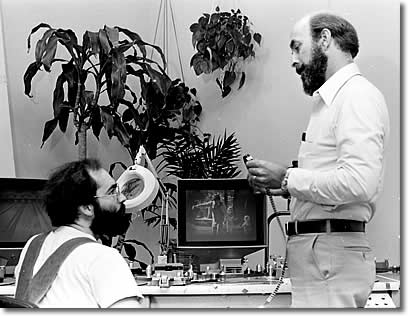

| Reno Bailey, Film Production Manager, right, checks with editor Barry Stillwell on the progress of an editing job for a complicated assignment. Bailey says editing jobs handled primarily on film are often of higher quality because editors don't feel pressured to wrap it up early as they sometimes do when the cost of videotape editing time is mounting. |

Bob Newcomb, Jefferson director/

photographer, and Joe Caruso, a free-lance director of photography, teamed with five other crew members on that three-day shoot. Three cameras running simultaneously captured the action as a Capri challenged the rough terrain. A 35 mm Bell & Howell Eyemo camera was positioned in a pit to provide a ground-level view of the car leaping skyward from a built-up dirt ramp. Two Arriflex 2C cameras followed the action from other angles. The spot was produced with Eastman color negative film 5254.

Today the same commercial would be filmed with the newer Eastman color negative IC film 5247.

Jefferson sometimes overexposes negative film and has it underdeveloped for high-quality, low-grain images. "Outdoors we usually shoot with an 85 filter at an EI rating of 32 rather than 64," Newcomb says. "The film looks a little flat when projected but snaps right up on a television system."

Concept work and customer approvals are left up to the advertising agencies, while Jefferson concentrates on the technical details and behind-the-camera creativity that can add that extra sparkle to a storyboard or script.

The variety of assignments handled by Jefferson helps keep the creative juices flowing. A random sampling of recent jobs includes an intricate tabletop shot demanding lots of overcranking and intricate lighting, a choreographed commercial during which bank employees break out in song and dance, and a dramatic sunrise shot for a power company.

"For the tabletop product shot, we relied on high-speed filming to capture bottles falling while various lights played up and down," says Newcomb. "For the power company spot, we shot a sunset, rather than a sunrise, in order to lock in on the sun at the horizon. We filmed one frame every three seconds and had it optically printed in reverse to create the sunrise effect."

Bailey says the film unit's work is no more, or less, complex than most other film company's efforts, and its techniques are fairly standard in the industry.

"Everyone shoots a lot of takes," he says. "The simplest scene, such as breaking an egg into a pan, can require a large number of takes, while the most complex shot may require only a few.

"Jefferson's edge lies in its ability to offer consistent quality regardless of the commercial style or subject," he continues. "We haven't been pigeonholed as specialists with food, or 'real' people interviews, or car commercials. We do them all and enjoy the variety"

As Bailey points out, filming is just one of the creative inputs needed to produce a top-quality commercial. Editing often is just as important.

"Often it's easier and cheaper to edit a complicated piece on film than tape," he adds. "Using a $15,000 flat-bed editor, one can afford to take the time necessary to do a complete, polished editing job."

"If you're working in a tape facility with expensive equipment and a large crew, you keep thinking about the dollars each hour can cost," adds Newcomb. "This pressure can tempt an editor to say 'it's good enough' and let it go. With film, the editor is more likely to take the time to distill the work and make it as good as possible."

Whether it's less expensive to produce a tape or 16 mm film often correlates to editing demands, says Bailey. A one-day shoot requiring five days' editing can be handled less expensively on film, while a one-day in-studio shoot needing little editing usually can be done on tape at less cost. Film again enjoys a cost edge if assignments require shooting in many locations or unusual ones, such as coal mines or underwater, he adds.

|

|

In the company's roomy studio Bailey discusses a set going up with carpenter Rick Pressley. Among Jefferson's competitive advantages is its ability to find locations and build sets at a lower cost than would be feasible in a larger metropolitan area. |

With the rise of the 30-second format, which now dominates the TV scene, editing and distribution are very important. And 10-second commercials, introduced along with abbreviated news break packages, are currently making in-roads, Bailey notes.

Jefferson Productions' 35 mm and 16 mm film mix is gradually changing, too. The 35 mm work—now about 40 percent of all Jefferson film commercials—is growing for two reasons, says Bailey First, the economy is in better shape and, second, the company is attracting clients who have more money to spend.

For top quality, Bailey feels 35 mm negative can't be beaten. He attributes the quality edge to the combination of a large fine-grain negative film and superior 35 mm camera lenses. Bailey sees the uptrend at Jefferson of 35 mm film as one element in advertisers' quest for commercials that can grasp and hold audience attention.

"With each passing year, it is necessary to do more to hold the TV viewer's interest," says Bailey "As a result, the ads we are seeing are much more creative—especially institutional commercials which are laced with comedy or use beauty as a focus.

"The demands of producers and art directors haven't changed," he concludes. "I think film's image as the creative medium among advertising agencies is as strong as ever."

From 1974 until the mid 1980s, the film department occupied a 6000 sq. ft. space in an industrial park on Pressley Road in south Charlotte. To the rest of the corporation we were pretty much out-of-sight, out-of-mind, and largely on our own. Not many outside Jefferson Productions knew about us. Advantages: casual dress, fewer meetings. —Reno Bailey