The staff of Jefferson Productions, to most everybody else in the company, was “those weird folks way down the hall, who wave at us when we go home at five.”

The staff of Jefferson Productions, to most everybody else in the company, was “those weird folks way down the hall, who wave at us when we go home at five.”

JP, as it was called, was what is called in the trade a “production house” that would deliver, on tape or film, whatever a customer needed—within reason.

It evolved in the 60's as an adjunct to WBTV's regular operations, as an additional service that could be sold, using the large staff of engineers and production people, and the WBTV studios, which sat idle some of the time.

The venture was so successful that it soon required it own crew, then soon got its own dedicated, fully-equipped studio in a new wing of the building.

In its first years, for awhile, Jefferson Productions was unique—a full-service video facility, with few like it outside of New York, Chicago and Los Angeles. It offered everything needed for a succesful production: set-building, props, actors and talented directors, editors, lighting and camera men, and technicians. All experts in their field.

In its first years, for awhile, Jefferson Productions was unique—a full-service video facility, with few like it outside of New York, Chicago and Los Angeles. It offered everything needed for a succesful production: set-building, props, actors and talented directors, editors, lighting and camera men, and technicians. All experts in their field.

JP maintained ts original identity—as a producer of recorded programs and commercials, and renter of mobile-unit equipment—for about 20 years. In the late 1980's it changed to producing only sports-related programming. In 2006 Jefferson-Pilot Communications sold out, and what we knew as JP became Lincoln Financial Sports. A year later, it was sold again, and it became Raycom Sports.

Few of the JP-produced commercials were ever seen by employees in other departments of the company, since most were for broadcast in other cities. If a spot did happen to air in the Charlotte market, few would recognize it as having been made at JP.

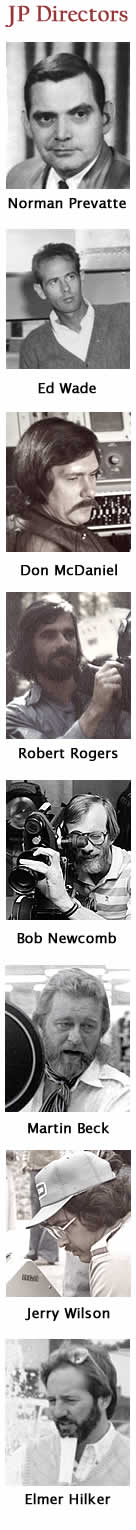

The team of talented professionals required to make a good commercial is headed up by the Director. There were many of them over the years at JP, including Norman Prevatte, Don McDaniel, Ed Wade, Robert Rogers, Bob Newcomb, Martin Beck, Elmer Hilker, Jerry Wilson and possibly more. Some worked in the film medium, some in videotape, and some in both. We've obtained a reel of 20 or 30 videotaped spots from the early 1980's and chose 11 of them for inclusion in this little trip down memory lane. They are fairly representive of our work in those years. As we come across more, we'll include them.

Enjoy.

In its first years, for awhile, Jefferson Productions was unique—a full-service video facility, with few like it outside of New York, Chicago and Los Angeles. It offered everything needed for a succesful production: set-building, props, actors and talented directors, editors, lighting and camera men, and technicians. All experts in their field.

In its first years, for awhile, Jefferson Productions was unique—a full-service video facility, with few like it outside of New York, Chicago and Los Angeles. It offered everything needed for a succesful production: set-building, props, actors and talented directors, editors, lighting and camera men, and technicians. All experts in their field.

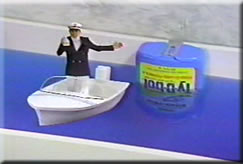

But often new items had to be built. We had a marvel of a woodworker, Floyd Grass, who could build anything. Sketch out a diagram on the back of an envelope—he'd build it: kitchen cabinets, boats, desks, ornate furniture, whatever.

But often new items had to be built. We had a marvel of a woodworker, Floyd Grass, who could build anything. Sketch out a diagram on the back of an envelope—he'd build it: kitchen cabinets, boats, desks, ornate furniture, whatever.

liquid laced with some chemical, which, upon being introduced to the liquid (laced with a different chemical) in the other reservoir, would immediately produce heat and smoke. But which chemicals? Assistant Producer Janice Crews was dispatched to find out. She consulted a pharmacist at a local drugstore who identified the chemicals needed. He actually sold her a supply.

liquid laced with some chemical, which, upon being introduced to the liquid (laced with a different chemical) in the other reservoir, would immediately produce heat and smoke. But which chemicals? Assistant Producer Janice Crews was dispatched to find out. She consulted a pharmacist at a local drugstore who identified the chemicals needed. He actually sold her a supply.