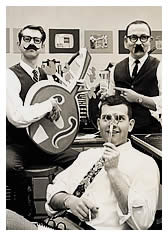

A trio of WBTV's crack graphics staff in a rare display of impromptu frivolity. Ordinarily they sat motionless at their desks, bothering no one, then, at 5:00 o'clock, they quietly went home.

A trio of WBTV's crack graphics staff in a rare display of impromptu frivolity. Ordinarily they sat motionless at their desks, bothering no one, then, at 5:00 o'clock, they quietly went home.

Here's a little show of about 100 old station-break slides from the '60s. And in the "Scroll of Fame" there are names of some of the people who, over the decades, labored long and hard in WBTV's graphics department. They done good. See if you remember some of these slides.

Play the Slide Show »

As a kid, it was always a mystery to me how TV stations put those still pictures on the air. Did they put photos and artwork on easels and "shine" a studio camera on them? What an awful waste, tying up an expensive camera for something as insignificant as a station break. It was only later, after I was initiated into the broadcasting fraternity (hired) that I learned what a film chain was, and that all those "stills" were actually slides, created by a staff of X-Acto-nicked, T-square-toting men and women in the art departments of the local stations and the networks.

|

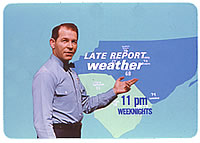

| "Catch Dick Taylor's weather on the Late Report, tonight at 11:00 here on WBTV." |

The order would come down from the Promotion Department to create a station ID slide for a local or network show, a community event, or just another variation of the station's call sign and channel. A graphic artist would spend many minutes, perhaps an hour or two, depending on the complexity of the job, selecting or creating a suitable background, cutting and pasting onto it an original sketch or photo of the show's cast, along with the typeset title and station id, mounting and aligning the finished art on a camera stand, and photographing it on positive film.

Once the roll of film was developed, the artist would snip out the desired frame from the strip of film, carefully place it between two squares of glass, and finally seal the edges of the "sandwich" with thin strips of sticky tape, to secure the frame inside the glass.

That little glass sandwich would be numbered, catalogued, filed, scheduled, and then loaded onto a film chain dozens of times over a period of weeks or months. And each time the projectionist had to inspect and clean off any fingerprints, lint or grime. And the videomen, like Harvey Hood, Lee Jenkins, or Cliff Whitney, would, each and every time, have to adjust the brightness, color and contrast of the darn thing before it went out over the air. Sometimes a slide would literally wear out, or more likely break, so it would have to be mended or done over.

The artists would create hundreds of these little slides per year. And simultaneously, slides would pour in by the hundreds from the networks, the syndicators and movie distributors, and these would also have to be numbered, catalogued, filed and scheduled as well.

And all this slide work was only

a small part of the artists' jobs. They were also responsible

for designing and producing logos; letterheads; company

publications; signs; exhibits; billboard art; newspaper

layouts; show titles; credit crawls; sets; and anything

else of a graphical nature that might pop into the heads

of management.

What these guys and girls would have given for a desktop

computer and a copy of Photoshop. Nowadays, we'd guess,

such visual artistry never sees the light of day, is

never touched by human hands, but is just strategically-arranged

clumps of pixels stored on humongous hard drives, with

all the properties set and forgotten, and is good

to go when the master computer says so. The days of

projection slides, like buggy whips, are long gone.

| —R.B. |